I’VE SPENT a good bit of my time asking people questions. Since my early twenties, I calculate, I’ve interviewed well over a thousand people, sometimes briefly, sometimes (for a book) for weeks on end. I was writing about the subject, or something connected to them, and my goals were to learn as much as possible as quickly as possible; to find ways to fit what I was learning into a story structure (beginning/middle/end); and, in the case of magazine articles, to elicit “good quotes”— words that readers would find engaging in a title or subtitle, or between big quotation marks on a print-heavy page. Along the way I’ve learned useful lessons, many of them long extolled by experts on the subject, others less obvious.

First off, it is self-evident that good interviewing demands way more listening than talking, but I emphasize the point here because ego prompts certain writers (myself included) to demonstrate that they’ve done research, they know some of the same people, and they, too, are interesting human beings. True, you want a session to feel more like a lunch conversation than a police interrogation, but you must keep in mind that, by definition, the subject is way, way less keen to know what you have to say than vice-versa.

So that’s rule number one—talk less, listen more. Here, in no particular order, are some others:

ASK OPEN-ENDED QUESTIONS

Don’t presuppose an answer in the name of empathy or alignment:

“You must’ve been really terrified when it got dark and you realized you were lost.”

You may be putting the subject in the position of needing to contradict you, which they may be reluctant to do. “Actually, I wasn’t scared at all. I was kind of excited. I knew I was in no real danger, I had water, I had matches for a fire, and worst case was that I wouldn’t sleep much and I’d find my way out in the morning.”

That’s why the better question is this:

“How did you feel when it got dark and you realized you were lost?”

ONE QUESTION AT A TIME

“What did you do to turn the company around in a year, and what was your reaction when the first-quarter numbers came in, and everyone finally started to see the potential in online sales?”

You’re wanting way too much. Your subject is never going to serve up all that you’ve asked for. It’s like email—if you ask three unrelated questions in an email, often only one or two get answered. Separate emails for separate questions. Similarly, in an interview, a single, simple question helps the subject stay focused:

“How did you turn the company around in a year?”

LET THE SUBJECT KEEP ROLLING

When a subject stumbles, or pauses, or runs out of steam, don’t say:

“It’s funny you should mention that, because the same thing happened to me when I broke my wrist playing baseball and got back on the field before I should have.”

Say nothing. Even if it gets a bit uncomfortable, wait. Let the subject resume. If they don’t, try something like this:

“Tell me more about sitting out that whole season.”

LET THE SUBJECT GO OFF-PISTE

You might have 20 questions you need answered, but they may not be the ones your subject thinks are germane. As long as you end up with the answers you need, don’t keep course-correcting. Let the subject steer the interview now and then and see where it takes you.

WINE IS GOOD

In a sense, you need to seduce your subject. Surprise: alcohol loosens lips and inhibitions. It creates a warm, enveloping bubble that can enhance candour and intimacy. When possible, schedule interviews for late in the day. Bring a decent bottle of wine as a gift and, if appropriate, open it. Questions or topics your subject may dodge at the outset often get addressed a glass or two in.

SWITCH OFF YOUR DEVICE

If a subject has agreed to, say, 30 minutes, and you turn off your recorder and make to depart at the appointed time, they may forget the half-hour agreement and really crank it up. Some—maybe even much—of the best material you get in interviews comes after the subject thinks the session is over.

USE SUPERLATIVES IN YOUR QUESTIONS

“What were some of your experiences in the Air Force?”

General questions like that leave too much latitude for sloppy reminiscence and banality. Make your subject narrow their answer by focusing your question. You’re looking for peaks, not expansive, boring flatlands. So, this instead:

“What was the single worst experience you had in the Air Force?

Have you done well financially?

“What’s the most money you’ve earned in a year?”

“Have you enjoyed pretty good health all your life?”

“What’s the closest you’ve ever come to dying?”

RECORD AND TAKE NOTES

“Gary, what was your worst interviewing experience?” (Note the superlative.)

In the 1980s, as a writer and editor at Saturday Night magazine in Toronto, I learned that the American anti-war activist and counter-culture hero Abbie Hoffman—one of the so-called Chicago Seven—had long evaded U.S. authorities by hiding out in the Thousand Islands region of the St. Lawrence River, just over the U.S. border in Canada.

I was able to reach Hoffman and commission him to write a memoir of his time on the run. He was in need of cash, so we advanced him half his (as I recall) $5,000 fee. His deadline came and went. He turned down my offers of taking a look at what he’d produced to date, and I began to suspect that he hadn’t written a thing. Having promoted the piece, and having reserved half a dozen pages in the issue already in production, we (especially I) would have looked stupid if it fell through. I went to Manhattan, where Hoffman was then living, to help him “complete” his memoir.

I flew to Newark, checked in to a hotel near the United Nations (magazines in those days had travel budgets), and reached Hoffman on the phone. I arranged to see him the next day, Sunday, at noon.

When I knocked on the door of a Midtown apartment, it was answered by Hoffman’s then-girlfriend, Johanna Lawrenson. I remember being struck by what an unlikely pair they made. He was a short, scrappy, bearded, Jewish shit-disturber; she was a tall, gracious woman, easy on the eye, the sort of lovely, lanky beauty you might have found on Mick Jagger’s arm.

Johanna was the daughter of Helen Lawrenson, whom I knew to be a Conde Nast journalist and socialite. Johanna’s mother had moved among New York’s elite, rubbing shoulders at Upper East Side dinner parties with the likes of Bernard Baruch, Claire Boothe Luce, and Conde Nast himself, whose magazine empire included Vogue, Esquire, Vanity Fair, Architectural Digest, and Town & Country. She’d made her name with racy articles such as “Latins Are Lousy Lovers” and “A Few Words About Fellatio.”

(Before long, the Abbie-Johanna pairing seemed less strange when I learned that her father, Helen’s third husband, was actually a labour organizer who founded the National Maritime Union, that Helen routinely eviscerated New York high society and had been a Communist spy in South America, travelling there under the guise of writing travel stories.)

In the Midtown apartment, we three had coffee and bagels. When brunch was done, it was interview time. Hoffman indicated that we should sit side by side on the sofa. I took out my recorder and positioned it between us.

“Do you like football?” he said, and switched on the TV.

“I love NFL football. I’ve spent more time watching than I like to admit.”

“Giants and Jets.”

As the game kicked off, I plugged the external mic into my recorder, pressed START, and began questioning him. Before long it became clear that my inquiries were distractions from the central purpose of the afternoon, which was to watch the battle of New York’s two NFL teams.

At one point the phone rang and Johanna popped in to say, “There’s a reporter from the Times who wants—”

“Not now, baby, the game’s on.”

We watched not just one football game that day but two, back to back, stretching over many hours. Johanna brought food and drink. By the time the second game ended, it was after 7 p.m. In fits and starts, slipping in questions and flicking the recorder on and off at breaks, I’d filled three mini-cassettes—six sides, 30 minutes per side. It seemed like lots of material but it also felt scattered and unsatisfying. At least I’d formed a very rough outline in my head of how the piece might work. Now I had to go painstakingly back through the tapes and piece together the details. I said my thanks and took my leave.

Back in my hotel room, I put the first cassette in and hit PLAY. The little wheels turned, but the recorder issued only a flat, crackly bbbssszzzzzzz. Nothing. Blank. Fuck. Maybe I’d mixed up the cassettes. Please God. Another cassette: bbbssszzzz. Each side of each cassette made exactly the same buzzy noise. I didn’t have a damn thing. I hadn’t even scribbled any notes.

Shame, embarrassment, and panic are not a happy mix of emotions. Once I’d calmed down, I realized I had four choices. 1. Start scribbling whatever I could recall of six hours of fractured conversation. 2. Phone Bob Fulford, the magazine’s editor, at home and tell him that I’d had, uh, technical issues and hoped we had something in the bank to fill the pages. 3. Call Hoffman and bravely, abjectly plead for mercy. 4. Leap to my death from the 30th floor.

I picked up the phone and dialled.

“Johanna, sorry to call so late, it’s Gary Ross. Is Abbie available?”

He came to the phone. “What’s up?”

“You’re not going to believe this. . .”

“Your recorder didn’t work.” Amazingly, uncannily, it was a statement, not a question.

“It’s crazy, I know, I’m sorry, I didn’t realize when you use an external mic you have to flip a switch on—”

“Extra five hundred?”

“Sorry?”

“Another five hundred bucks.”

“Oh right, of course, the magazine would be happy to top up your fee for more of your time. When can I swing by? My flight’s at 2 p.m. tomorrow.”

“Nine a.m. I have to see my lawyer at 11. Bring some stuff from the deli.”

On Monday morning, a wonderful thing happened. Without football to distract him, Hoffman rose to the occasion. Having done a sort of raggedy run-through, and having thought about it all night, I had a complete outline in my head. I knew exactly where specific anecdotes belonged, and I guided him toward each place the narrative needed to go next. He answered questions candidly but judiciously (he still had legal woes), with just the right dose of anti-capitalist rhetoric and renegade bravado.

An hour later, we were done. (It would have taken me five times as long if my recorder had actually worked.) Transcribed and polished, that second interview, absent the questions, turned out to be not so very different from the 5,000-word memoir that appeared in the magazine. He’d practically recited his first-person narrative verbatim.

I’d learned another lesson. Make sure your recorder works. Test it once, test it twice. (Some writers I know use two recorders.) Also, take notes as you go, even brief, shorthand ones, the way you might blaze the occasional tree to mark your way through the woods. Notes remind you at least of the general drift of the interview.

That’s how I ended up doing the worst interview of my life, and then maybe the best, in a space of less than 24 hours. I also learned another thing that’s held true ever since. A follow-up interview is often more helpful than the first session. That’s why I make a point of asking, after every interview, “OK if I get back to you with more questions?” Nobody has ever said no. And lots of people have really opened up the second time around.

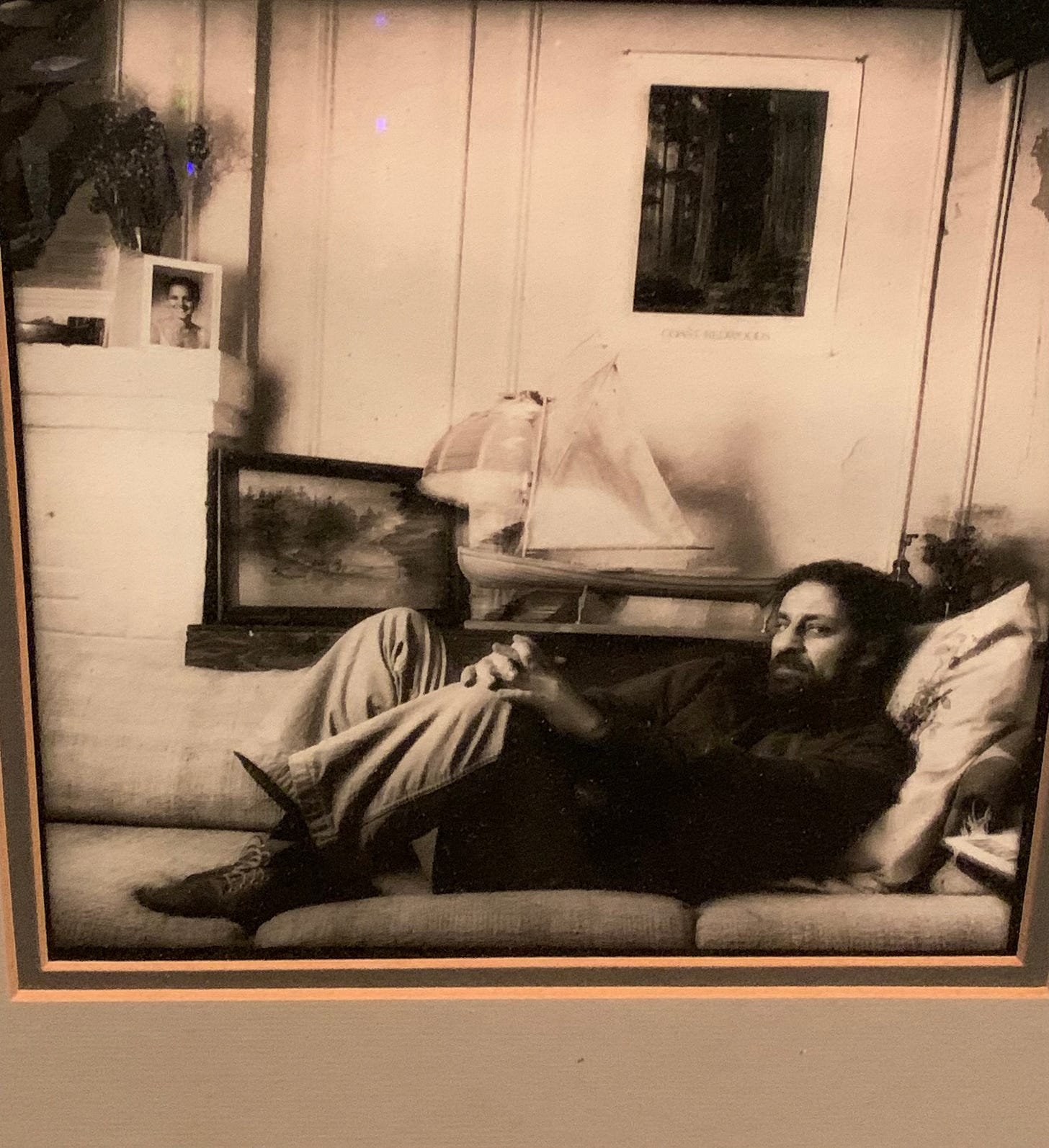

P.S. 1. The photo of Abbie Hoffman above was taken by the great Nigel Dickson.

P.S. 2 .All this reminds me of interviewing the late hockey star Gordie Howe, in Hartford, Connecticut, for a magazine profile. Those sessions, conducted sporadically over three days, were also full-blown disasters, though for other reasons. I’ll save that story for next time.

P.S. 3. This week’s gold star goes to SpaceX, for explaining that their spacecraft Starship didn’t blow up, but rather suffered a “rapid unplanned disassembly.”

Hi Gary -- Good tips. Wish I had read these 40 years ago.... I had to learn on the job the hard way about making sure your recorder was on and making sure to take notes.

I loved Q&As. During my long and undistinguished journalism career in newspapers, I did hundreds of interviews by phone or in person with newsmakers, authors, think-tank gurus, celebrities, politicians, movie stars -- everyone from Nikita Khrushchev's son to Newt Gingrich to Depak Chopra to Ted Sorensen to Tucker Carlson to Jimmy Stewart to Milton Friedman.

Many of them are dying off or reappearing in the news, which, if I can outlive them, gives me a chance to re-run them on Substack. https://clips.substack.com/s/q-and-as-interviews-with-the-smart

Before I did a Q&A by phone I'd write out my questions longhand on a legal tablet and then number them in the following order:

No.1 was an obvious opening question, hooked to a news event or a book the person might have written.

Next were a bunch of questions that could be asked in almost any order as part of the conversation.

Last was an obvious final ‘What now?’ or ‘What’s next?' question that looked to the future or wrapped things up.

I did one of these Q&As for the Pittsburgh Tribune Review's Opinion section every Saturday for about eight or nine years — about 400 total, I figure.

I had to transcribe every interview -- each probably 1,000 words -- and then boil/edit it down to fit a certain length. When we were able to put the interviews on the Internet, we posted both the full interview and the shorter for-print one.

Most times I had to do some gentle editing to make sure everything made sense. But Milton Friedman at age 89 spoke so clearly and succinctly, I don’t think I had to add or subtract a word.

For them that's interested, this link has an image of my scribbled Friedman questions.... https://clips.substack.com/publish/post/34958560

Glad Stephen Kimber told me to sign up, or maybe it was David Hayes(!) As a journalist I enjoyed this. Love the superlative question. I always have a second recording going on if I can. Also, people talk more when walking. Just my finds. Looking forward to your next piece. May I suggest something on how to rebuild rejected pitches? It's really really tough right now as a freelancer and even though I'm a good seasoned journalist, I'm not a known name in Canada and rejections come hard and fast. I want to be able to re-use all the time/effort I put into researching rejected pitches.