I’VE BEEN AWAY from this space for a bit because I’m engrossed in a new project. I’m helping a financier tell his life story, which is fascinating, complicated, and traverses many fields. The project requires much online research, interviews with a growing list of secondary characters, and many, many hours with the subject himself.

Of the two quite different types of books I’ve written—my own, and other people’s—friends assume the former satisfies my creative soul and my ego, the latter my bank account. In a way that’s true, I guess, but it’s a gross oversimplification. My own work comes from my experience, imagination, and research. (I have a new novel that looks as if it will be published next spring.) My own books bear my byline. Someone else’s book—one I’ve ghostwritten—might name me in the acknowledgments, or in small print on the back cover, or not at all. In any case, it passes as the work of the subject.

YET RARELY IS ghostwriting the kind of drudgery some people assume it to be. For one thing, it’s a privilege to be invited into the depths of someone else’s life, the inner precincts of the heart, their trove of filed memories. It’s a privilege usually granted only to lovers and therapists. For another, I try to choose projects that require me to learn something I don’t know much about. In essence, I don’t just get a free education, I get paid to understand new things.

How geologists find valuable mineral deposits, for example, and how those deposits get developed into mines (many millions, years, and permits). The way wealthy Hong Kong Chinese view Americans (as bellicose, ignorant of the world, and deluded about the virtues of their own country). Why one restaurant chain succeeds where another may not (culture-building, intensive training, abundant career opportunity). How automobile dealerships thrive (own the real estate and create a balanced income stream from new-car sales, used-car sales, and servicing).

I’ve gained insight into how billionaires exert influence, how Hollywood movies get made and distributed, how brokerage firms make money, and the economics of a shopping mall. I have a good sense of what it’s like to be a Lutheran dentist in the U.S. Midwest, the president of a CFL team that’s always on the verge of going broke, and a wrongly convicted man in a maximum security penitentiary. These are all things I’ve learned in the course of helping other people write their books.

An outstanding memoir. Another is Life, by Keith Richards with James Fox.

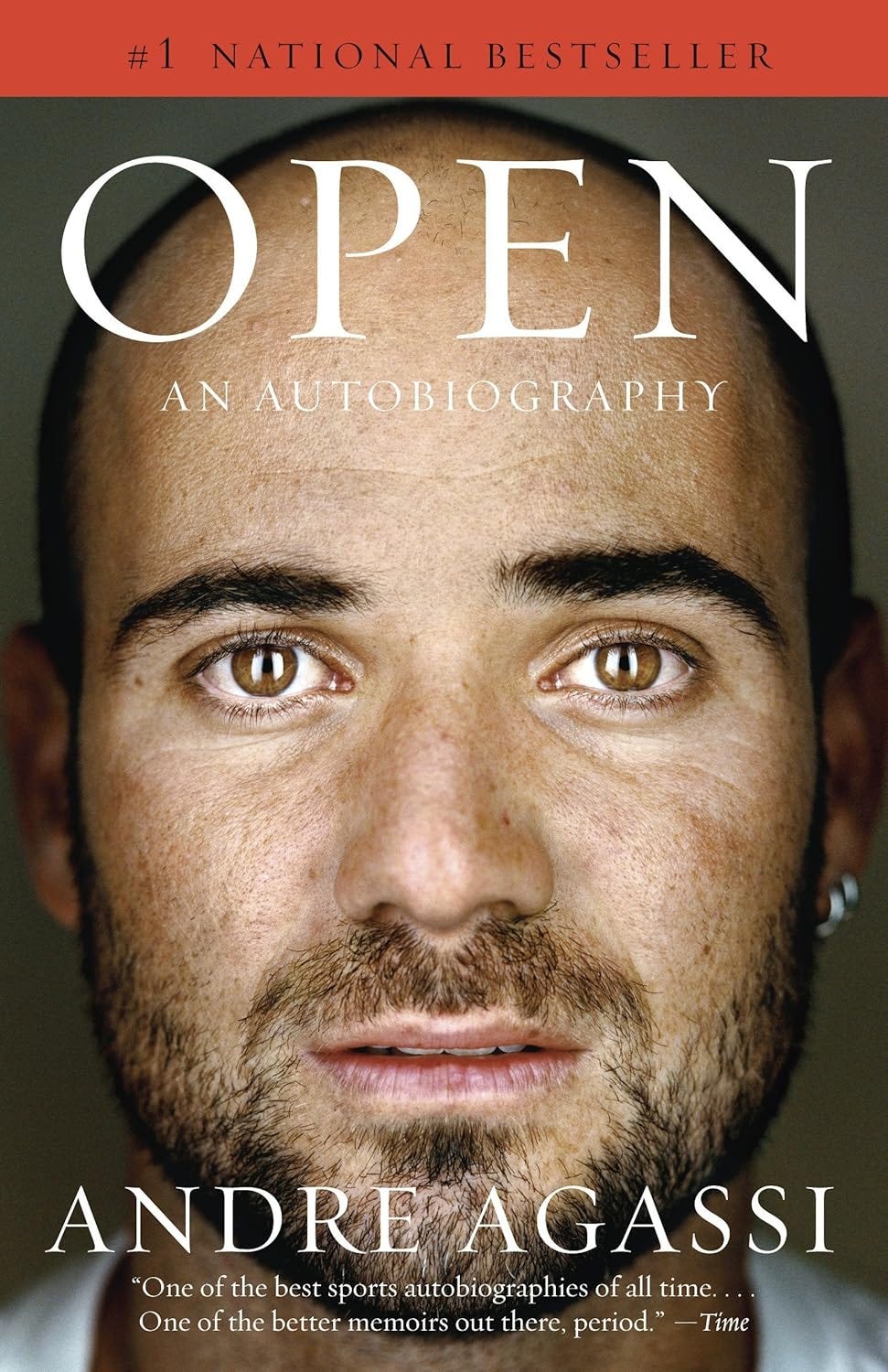

JUST ABOUT every bestselling book by an athlete, celebrity, or politician was written by a ghostwriter. The best such book I’ve read is Open, Andre Agassi’s memoir, which was written by J. R. Moehringer. In this ideal collaboration, Agassi recounts his dysfunctional upbringing, his rise to tennis stardom, and his personal life with, at times, almost painful vulnerability.

The bond of trust and intimacy that Moehringer built with him is evident throughout. The voice on the page, though hybrid, seems Agassi’s own. You end up admiring, even loving the guy, imagining what a lovely friend or partner he’d make. (He’s married to Steffi Graf, another former tennis great.)

Moehringer also worked with Prince Harry on Spare, a memoir I started reading, then dipped into, then put aside. It wasn’t just my relative lack of interest in all things royal. The book fairly bristles with arresting incident and detail, and Harry’s life has been fantastically rich and eventful. Spare quickly became one of the bestselling nonfiction titles ever, and prompted much debate about the appropriateness of its disclosures and Harry’s motives in seeing it published.

Though the book was touted as being “shockingly candid,” those disclosures—how he lost his virginity, for example, skullduggery in the royal household, who leaked what to the media, how his penis was once frostbitten, others’ reactions to his mother’s death, his kills in Afghanistan—seemed more forced and even icky than emotionally resonant.

Either Harry lacks Agassi’s depth and expressiveness, or Moehringer was not quite able to tap into it. I was never convinced that the voice was Harry’s. The writerly tricks Moehinger used to spice things up, tabloid-style—quick cuts, one-sentence paragraphs, two-word sentences) only added to this dissonance. For all the whiz-bang moments in Spare, all the voyeuristic glimpses, royal agonies, occasional pettiness, and “shocking candour,” Open lingers in my mind as the more candid, sensitive, and revealing book.

Hmm. Wonder where the publishers got the idea for the cover design. . .

TO PROMOTE Spare (and himself), Moehringer published a piece in the New Yorker about working with Prince Harry (and Agassi, and Phil Knight, the founder of Nike, and about his own life, and about ghostwriting in general). I read the piece with baffled curiosity—baffled because I’m required with each ghostwriting project to sign a non-disclosure agreement preventing me from doing just such a thing. Presumably, then, Harry approved the piece.

Moehringer, who tells us he’d intended to stay far from the limelight, had already been outed as the ghostwriter, so why not capitalize on the moment? More power to Harry, I guess, for giving his blessing, given that he doesn’t always come across admirably in the piece. In the end, the two resolved their differences, and the article served as chum to draw the media back into the water.

Lots of ghostwriters have horror stories of the professional relationship unravelling. I’ve not been fired from a ghostwriting job—I’ve never even seriously butted heads—but a couple of my friends have been. Even then there may be unexpected rewards. One pal was informed that the subject had changed his mind about doing a book when they’d only just got seriously underway. Would my friend accept $70,000 as a kill fee instead of the agreed-upon $90,000? (He did, gratefully, which perhaps helps explain why he’s a freelance writer and not the sort of legal shark who’d say, "Absolutely not! A contract is a contract.”)

Men’s doubles: Moehringer and Andre Agassi turned out to be an ideal pair.

I RECALL MY friend Bruno, when he was renovating my place many years ago, talking about the sudden intimacy of stepping into the middle of someone’s life. A house, in some ways, is a life in microcosm. A renovation exacerbates tensions, requires decision-making, has financial implications, exposes people’s values. Decisions made under pressure reveal character. Renovating someone’s house, said Bruno, shows you who the inhabitant is. If you’re lucky as a ghostwriter, you’re allowed to enter into your subject’s life in the same immersive way. I’ve made ongoing friendships with people whose books I’ve written.

If the best writing is an attempt to get to the heart of things, the best ghostwriting is a frank partnership aimed at recounting, revealing, and reflecting honestly on a heartfelt life. It requires not just the subject’s willingness to reveal himself, warts and all, but also his blessing to interview those closest to him, since others in some ways know us better than we know ourselves.

It’s also a great help to see your subject in action. Telling someone what you did and how you did it is one thing. Shared experiences enable a deeper level of understanding. One lovely fellow whose book I did, a geologist who’d played a role in discovering what became the Cyprus-Anvil mine in the Yukon, had a helicopter company based in Whitehorse. He took me on a tour.

From the air, the beauty of the Yukon in September is unforgettable: deep evergreen valleys, expansive yellow carpets of aspen draped over entire mountainsides, the pure white of Mount Logan against the bright blue sky. Gordon delighted in pointing out a geological feature, an old drill site, a trip of mountain goats on a cliff face. Seeing him in his element spoke to his love of wild places and mineral exploration in a way that words, from interviews at his office or his home, simply could not.

MY CURRENT SUBJECT’S life has all the ingredients—rags to riches, hero’s journey, high-risk undertakings, big wins and losses, candid dealings with the rich and famous, personal growth, life lessons—to make a memoir people will want to read. The more time I have with him, the more he expresses himself with the easy, unforced candour that elevates the Agassi book. If I can structure his experiences in a way that keeps readers turning the page—as Moehringer does in his work—I’ll have done the job I’m being paid to do.

But more than that, I’ll have helped someone tell a fascinating life story that’s quite unlike my own. I’ll have learned things that make me wiser, more informed, more empathic. Every life, revealed, is full of unexpected lessons. For me, that’s the pleasure and reward of ghostwriting.

What a positive approach, and a productive and diverse way to learn. A very interesting insight.

I loved the explanation of learning and sharing, of vicarious experience leading to a broadening of understanding.